Image via Wikipedia

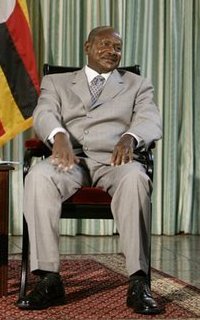

Image via Wikipedia"In April 2004, nearly a year after Mr. Moreno-Ocampo floated the idea of a Congolese case, Congo President Joseph Kabila referred alleged war crimes within his nation to the ICC. Mr. Moreno-Ocampo set up a separate team to investigate atrocities there, which will likely involve reviewing Uganda's alleged support for Congolese militias. President Museveni of Uganda asked U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan to block the Congo investigation, according to one person familiar with the matter..."

By JESS BREVIN

WALL STREET JOURNAL

June 8, 2006

THE HAGUE -- In August 2004, the International Criminal Court sent investigators to Uganda to gather evidence against a shadowy insurgency known as the Lord's Resistance Army.

It was precisely the kind of desperate case the world's first permanent war-crimes tribunal was set up in 2002 to prosecute, and court officials hoped to showcase a new brand of international justice. The Lord's Resistance had terrorized Uganda's Acholiland region with murders, rapes and child abductions. Over two decades, the insurgents had kidnapped more than 20,000 children and driven nearly two million people from their homes, the United Nations estimates.

But the ICC quickly discovered how difficult it can be to dispense justice in corners of the world where political, military and diplomatic forces have long failed to produce stability.

Seven months after ICC investigators arrived in Uganda, a delegation of Acholi tribal leaders came to the court's headquarters here with an unexpected plea: Drop the case.

Although the tribal leaders feared the Lord's Resistance and its messianic leader, Joseph Kony, they also were afraid that the ICC's vow to prosecute him left the rebel leadership little incentive to negotiate -- and every reason to fight on. Is the ICC "able to provide peace, or only justice?" asked David Onen Acana II, the paramount chief of the Acholi, during an interview last year at The Hague. "We want peace by any means."

The Uganda case, the ICC's first, has become a test of the fledging international court and its charismatic Argentine chief prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo. In January 2004, Mr. Moreno-Ocampo predicted arrests by year's end and a trial in 2005. But the ICC has no police force of its own, and its member states, including Britain, France and Germany, have shown no inclination to help Ugandan forces apprehend anyone. Today, not a single suspect is in custody and no trial date is in sight. To make matters worse, the unsealing of arrest warrants in October was followed by the killings of foreign aid workers in northern Uganda in apparent reprisal.

In recent weeks, Uganda's president, Yoweri Museveni, and Mr. Kony have engaged in an unprecedented public dialogue that threatens to cut the ICC out of the picture entirely. Mr. Museveni offered to shield Mr. Kony from prosecution should he surrender by July 31. And Mr. Kony, in a videotaped message, said he wanted peace.

Northern Ugandans displaced by the ongoing civil conflict have been resettled to government-controlled camps, sometimes forcibly.

"In Uganda, they have not done well," says William R. Pace, head of the Coalition for the International Criminal Court, which promoted the creation of the tribunal and continues to serve as an independent adviser. "I think there's blame on all sides."

Mr. Moreno-Ocampo says the court has suffered from growing pains, and that criticism and setbacks are inevitable, given its unprecedented mission. "It's like assembling the airplane, recruiting the crew and taking off," he says.

The ICC was established as an independent international tribunal, a court of last resort for humanity's worst crimes. One hundred nations, including Uganda, are members, providing funding and electing the court's judges. The U.S. isn't among them. The Bush administration contends the court's charter lacks safeguards against prosecuting Americans for political reasons.

RISING TENSIONS

Thus far, the court has struggled to handle multiple investigations on a lean budget. As lawyers from different legal systems try to work together under an untested code of international criminal law, there have been disputes within the ICC over such basic questions as which incidents to review and whether prosecutors or judges are ultimately in charge of investigations. The court has squabbled with some member states over priorities and hiring decisions. And tensions have developed with some of the human-rights organizations that nursed the court into existence and now feel shut out.

The ICC traces its roots to the international tribunal at Nuremberg that tried Nazi war criminals after World War II. Nuremberg led to U.N. proposals for a permanent successor court, but the campaign stalled during the Cold War. In 1993, the U.N. Security Council established a tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, followed by additional ad hoc courts for Rwanda, East Timor, Sierra Leone and Cambodia. Human-rights groups argued that a single permanent court to handle future cases would be more effective and less expensive.

In 1998, a U.N. conference in Rome drafted a treaty for the ICC. Thanks to strong European support, the treaty garnered the required ratifications from at least 60 nations. The court's member countries quickly elected 18 judges. Settling on a chief prosecutor, who serves a single nine-year term, took longer. After several candidates dropped out for personal or political reasons, the post went to Mr. Moreno-Ocampo in 2003.

In Argentina, Mr. Moreno-Ocampo, 54 years old, is a legal celebrity. From a military family, he gained fame in the 1980s for prosecuting Argentina's deposed junta. "His family thought he was a traitor. They stopped talking to him," says Hector Timerman, a former dissident journalist and now the Argentine consul general in New York. Supporters of the junta threatened to kill Mr. Moreno-Ocampo and his children, Mr. Timerman says.

Mr. Moreno-Ocampo created an anticorruption advocacy group and hosted a television program on the law. He defended Mr. Timerman and his father, the late journalist Jacobo Timerman, from lawsuits filed by powerful figures, including former President Carlos Menem. Later, he represented wealthy clients in disputes over family assets, filed shareholder suits and consulted on corporate-accountability issues. He was a visiting professor at Harvard and Stanford. Today, "he's probably the best-known lawyer in Argentina," Mr. Timerman says. "Every young law student wants to be Moreno-Ocampo."

Mr. Moreno-Ocampo says he took office aware of the shortcomings of prior U.N. tribunals, which have been criticized for their slow pace and high cost. "This will be a sexy court," he said in an interview last year. The court aims to bring a different case each year, he said, and to televise them across the globe from the ICC's high-tech courtroom. The goal: swift justice that is comprehensible to often-uneducated victim populations.

The ICC treaty, known as the Rome Statute, gives the court jurisdiction only over "the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole." The statute specified genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and "aggression" -- once a future diplomatic conference agreed upon a definition for that term. Anything that happened prior to July 1, 2002, was off limits. Unless the U.N. Security Council referred a case, the ICC could act only within its member nations, and only if one of them requested ICC action, or if the court determined that a member government was "unwilling or unable genuinely" to address a suspected crime. Even then, the Security Council could vote to block an ICC case for a renewable one-year period.

SONG AND DANCE

At a restaurant in The Hague, Cecilia Otim-Ogwal, a member of the Ugandan Parliament, leads a delegation of Ugandan tribal leaders and their host, ICC prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo, in traditional song. See the video. Credit: Jess Bravin

RealPlayer: Player required

At a July 2003 news conference, Mr. Moreno-Ocampo announced out of the blue that he "believed" atrocities in Congo, a member state formerly known as Zaire, could qualify for an ICC investigation. He had provided no advance warning to Congo's government or to any other member countries. "Diplomats make a deal before they speak publicly," says Mr. Moreno-Ocampo. "But I am not a diplomat."

Mr. Moreno-Ocampo didn't follow up with an immediate investigation. But his remarks worried Congo's neighbor, Uganda, which Congo had accused of invading and destabilizing its eastern territory. An attorney for Uganda met with Mr. Moreno-Ocampo in 2003 to deny his government was involved in atrocities in Congo, according to someone familiar with the matter. Discussion turned to Uganda and the Lord's Resistance. Eventually, an agreement emerged for Uganda to refer that matter to the ICC. Uganda's government saw the deal as a way to gain an international ally in its campaign against the Lord's Resistance.

Mr. Moreno-Ocampo planned to announce the agreement in a joint news conference with Uganda's President Museveni. But several ICC staff members objected to Mr. Moreno-Ocampo appearing publicly with Mr. Museveni, citing the Ugandan government's reputed involvement in atrocities in eastern Congo, according to one court official. ICC investigations chief Serge Brammertz, a Belgian career prosecutor, "was going bananas telling Luis not to do this, and he did it anyway," according to the ICC official. Mr. Moreno-Ocampo appeared with Mr. Museveni at a news conference in London. Mr. Brammertz, who is on leave from the ICC to handle an unrelated case, couldn't be reached for comment. Mr. Moreno-Ocampo declines to discuss internal deliberations, but says it was vital to get the Ugandan president's cooperation.

The prosecutor says he had never heard of Mr. Kony before arriving at the ICC. To the extent Mr. Kony's opaque ideology can be discerned, the self-described prophet seeks to impose on Uganda his own interpretation of the Ten Commandments. Mr. Kony built his insurgency by raiding villages to kidnap children, then indoctrinating them into his rebel army, sometimes after forcing them to kill their own parents, according to the U.N., human-rights groups and ICC investigators.

Raised in the bush to become fighters, porters or concubines, Mr. Kony's captives then abducted more children to replenish the ranks. "The victims become perpetrators," says Christine Chung, a former assistant U.S. attorney from New York hired by Mr. Moreno-Ocampo to try the case.

A recent U.N. security assessment reviewed by The Wall Street Journal describes Mr. Kony as a "pathological liar" who "believes his own myth" and "shows traits of both a narcissistic personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder." Mr. Kony is "incredibly difficult to deal with," the report says, in part because "he has no conscience whatsoever."

'I KNOW MY FATE'

Betty Bigombe, a former Ugandan cabinet minister who has held sporadic peace negotiations with the Lord's Resistance since the early 1990s, is among the few outsiders with whom Mr. Kony speaks. To his followers, he is a god, interpreting dreams, administering drugs, issuing commands on a whim, she says. But "sometimes he talks a lot of sense," she says. "One day I was talking to him, not too long ago, and he said, 'I know my fate. I have one of three options. One is death, one is prison, the other one is exile.' " Efforts to reach Mr. Kony through Ms. Bigombe were unsuccessful.

MORE ON THE ICC

Read the full text of the Rome Statute, the ICC treaty that gives the court jurisdiction only over "the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a hole."

See a video report on the swearing-in ceremony for ICC Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo at the Peace Palace in The Hague.

See Interpol's "Red Notices" or wanted bulletins for the top commanders of the Lord's Resistance Army: Ugandans Joseph Kony, Vincent Otti, Raska Lukwiya, Okot Odhiambo, Dominic Ongwen. Plus, general information on Interpol's bulletins.

ray ban outlet, prada handbags, tory burch outlet online, christian louboutin, michael kors outlet online, coach purses, coach outlet, christian louboutin outlet, kate spade outlet, burberry outlet online, christian louboutin shoes, longchamp outlet, nike free, michael kors outlet, polo ralph lauren, michael kors outlet store, jordan shoes, red bottom shoes, louis vuitton outlet online, burberry outlet online, longchamp outlet online, coach outlet, michael kors outlet online, louis vuitton handbags, oakley vault, oakley sunglasses, gucci handbags, polo ralph lauren outlet, tiffany and co jewelry, prada outlet, louis vuitton outlet, chanel handbags, louis vuitton, kate spade outlet online, nike air max, true religion outlet, michael kors outlet online, ray ban sunglasses, nike outlet, nike air max, true religion, cheap oakley sunglasses, longchamp handbags, louis vuitton outlet, coach outlet store online, michael kors handbags, tiffany jewelry

ReplyDeletewedding dresses, mac cosmetics, soccer shoes, soccer jerseys, canada goose outlet, insanity workout, canada goose, p90x workout, abercrombie and fitch, longchamp, nfl jerseys, ugg soldes, instyler ionic styler, giuseppe zanotti, canada goose outlet, reebok shoes, ghd, herve leger, nike huarache, ugg outlet, bottega veneta, jimmy choo shoes, celine handbags, ferragamo shoes, ugg, canada goose outlet, babyliss, mcm handbags, uggs outlet, asics shoes, north face jackets, lululemon outlet, north face jackets, hollister, marc jacobs outlet, replica watches, valentino shoes, uggs on sale, birkin bag, uggs outlet, nike roshe, vans outlet, chi flat iron, new balance outlet, nike trainers, beats headphones, ugg boots, mont blanc pens, ugg boots

ReplyDeletemoncler outlet, wedding dress, supra shoes, uggs canada, louboutin, coach outlet, canada goose, air max, ugg, lancel, moncler, converse, moncler outlet, louis vuitton canada, thomas sabo uk, moncler, pandora charms, canada goose, juicy couture outlet, links of london uk, swarovski uk, replica watches, juicy couture outlet, moncler, nike air max, swarovski jewelry, timberland shoes, montre femme, hollister, oakley, moncler, hollister clothing, ray ban, hollister canada, pandora uk, vans, pandora jewelry, baseball bats, ralph lauren, gucci, parajumpers outlet, converse shoes, moncler, canada goose pas cher, iphone 6 case, karen millen, canada goose, toms outlet

ReplyDeletezzzzz2018.10.26

ReplyDeletefitflops clearance

oakley sunglasses

valentino shoes

coach factory outlet

louboutin shoes

pandora outlet

moncler outlet

moncler jacket

moncler outlet

jordan shoes

ray ban sunglasses

ReplyDeleteugg boots clearance

louboutin shoes

valentino shoes

christian louboutin shoes

ugg boots outlet

asics shoes

christian louboutin shoes

coach outlet

reebok outlet

this pageher comment is here useful referenceview it now have a peek at this web-sitesite here

ReplyDeletemore tips here find more site web this content view publisher site go to this site

ReplyDelete